Missouri Chief Justice delivers 2021 State of Judiciary virtually

Vol. 77, No. 2 / Mar. - Apr. 2021

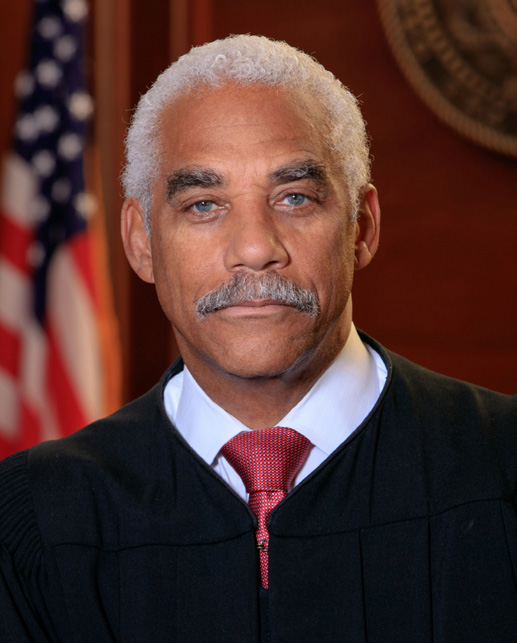

Hon. George W. Draper III

To all the statewide office holders, members of the 101st General Assembly, executive branch officials, and the judicial branch: Despite this year’s unusual format, thank you for your fidelity to cooperation among the branches of our state’s government and for this opportunity to present the state of our judiciary.

My parents were public servants, and my wife, Judy, daughter, Chelsea, and I have spent the great majority of our entire careers in the service of the public. For me, that includes nearly four decades as an employee of the people of the state of Missouri. I know you understand the rewards of public service as well or you would not be here today.

My parents were public servants, and my wife, Judy, daughter, Chelsea, and I have spent the great majority of our entire careers in the service of the public. For me, that includes nearly four decades as an employee of the people of the state of Missouri. I know you understand the rewards of public service as well or you would not be here today.

In this, our state’s bicentennial year, we stand at a crossroads of history. We can look back at the accomplishments of past Missourians and consider the future we want to build for our great state. And what a crossroads it has proven to be.

Never could any of us have imagined these stressful times, trying to maintain a sense of normalcy in our public work in the midst of national strife and a global pandemic. Our lives are not, and probably never will be, the same. To those who have lost family, friends, jobs and have themselves suffered illness as a result of COVID-19, I offer my sincerest condolences.

Bicentennial

For those of you who were here last year, you may recall I began by enlightening you about my personal history. In honor of our state’s bicentennial, today let me share with you some history of Missouri courts.

Our state judicial branch first was formed when Missouri adopted its first state constitution in July 1820. The state’s first governor appointed the first Supreme Court judges in November 1820, and the Court held its first session in March 1821 in the town of Franklin. All of this occurred before Missouri officially entered the union in August 1821, under the Missouri Compromise. As the population grew, so did the number of judges on the Court, increasing from three to five in 1872 and the present number of seven in 1890. Once an intermediate appellate court became necessary, the first was established in 1875 in St. Louis, with expansion to Kansas City in 1884 and Springfield in 1909.

It might surprise you that the Court was homeless for nearly 40 years. The constitution originally required Supreme Court judges to “ride the circuit,” traveling to hear cases throughout the year. In 1875, the constitution required the Court to sit only in Jefferson City, and state prisoners built the first Supreme Court Building in 1878 approximately where the Department of Transportation now sits. By 1905, construction was underway on our red brick building. Excess appropriations from the 1904 World’s Fair in St. Louis were used to complete the project, and the Court held its first oral arguments in the new building we now call home in October 1907.

As is the case with most history, not all of it was positive – especially during the turbulent years of the Civil War. In February 1861, the legislature called for a state convention, which decided Missouri would stay in the Union. Just five months later, after the pro-secessionist governor fled the capital, the state convention delegates declared all statewide offices vacant and elected Hamilton Gamble – a former state Supreme Court judge – to be governor of the state’s Union-backed provisional government. During this time, courts were suspended, government buildings were burned, and a number of judges – including the Supreme Court’s three judges – vacated their offices after refusing to take a loyalty oath. The 1865 state constitution required an “ironclad” loyalty oath of all Missourians who wished to vote, teach, be trustee of a corporation – or hold public office – to swear they never had supported the Confederate States in any way or even spoken in favor of it. The United States Supreme Court eventually found such oaths unconstitutional, and by 1870, the oath requirement was removed from Missouri’s constitution.

Increased Diversity

Even before the Civil War, Hamilton Gamble had earned a unique place in history. Precipitating the war was the freedom suit involving the fate of Dred Scott. When the case came before the Supreme Court of Missouri, all three judges – including Hamilton Gamble – were slaveholders. Under longstanding Missouri precedent, the act of taking an enslaved person to a free territory resulted in the person’s emancipation. In their majority opinion, two judges overruled this precedent and denied Mr. Scott his freedom. Judge Gamble, however, dissented, saying the Court should follow the law and recognize Scott’s freedom. He wrote: “… in my judgment, there can be no safe basis for judicial decision, but in those principles which are immutable.” That was in 1852. Five years later, the United States Supreme Court dismissed a similar federal appeal, holding regardless of whether Mr. Scott was free or enslaved, as a Negro he was not an American citizen and could not sue in federal court.

Today, all those born in America are citizens regardless of the color of their skin. They can become lawyers, judges, legislators, even president or vice president. I understand your 101st General Assembly is the most diverse in history, more closely representing the Missourians back home you are here to serve. In the judiciary, our diversity is improving as well. Of the judges recently appointed under Missouri’s nonpartisan court plan, 14 have been women, judges of color, or both.

However, as events from the Ferguson protests through the racial unrest during the past year have shown, we still have work to do as a society. As designed, our legislative and executive branches are where we can take our arguments for changes in law and policy, and our judicial branch is where we take our legal disputes for a peaceable resolution. But our judicial branch does not work as intended if we are not trusted to provide a fair and impartial forum for all people to have their cases heard and decided.

In recognition of this constitutional imperative, we also continue the courts’ efforts to address implicit bias and institutional racism that exist systemically throughout our country. As of July 2019, all lawyers licensed in Missouri are required to include at least one hour of implicit bias training in their 15 hours of annual continuing legal education.

Missouri judges and court staff already were required to complete annual implicit bias training. Indeed, some may say ethics and morals cannot be legislated, but just like all of you in our great General Assembly are working to ensure citizens respect each other in person, the courts of Missouri will continue to prescribe conduct commensurate with the highest principles of professionalism and good moral character. Through our efforts, we hope to build a culture of respect and fairness, and a judicial system in which all persons are truly equal under the law. The people of Missouri deserve no less.

1918 – War and Pandemic

The Civil War, of course, was not the only moment in history with a profound impact on Missouri. Consider 1918, when most statewide office holders were required to register for the draft, including 39-year-old Supreme Court Judge Fred Williams. And as if the war were not enough, the world was also in the grips of an influenza pandemic. Ultimately, more than 675,000 people in the United States died, among at least 50 million deaths worldwide.

Doctors and the federal government struggled to explain its cause, how best to mitigate its spread, the best treatments, and whether, once infected, someone could be reinfected. As cases spiked, schools, churches, and public amusement venues were closed, and public gatherings were banned. Sound familiar yet? At least one Missouri town required those infected with influenza to obtain a physician’s certificate proving they had recovered before they could venture into public. At least two circuit courts, after conferring with local attorneys, adjourned their dockets. As one headline declared: “Too Much ‘Flu’ to Hold Court.” As the influenza abated, restrictions were eased and finally lifted around the turn of the year.

COVID-19 Pandemic

And that brings us to today. It is impossible to talk about the last year, let alone deliver this State of the Judiciary address, without recognizing the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. Like other parts of government, Missouri’s courts had to find ways to adjust and innovate in an incredibly short period of time. By mid-March, national and state emergencies were declared, and your Supreme Court of Missouri issued its first order addressing the COVID-19 pandemic. That order and every set of operational directives issued since have made one principle clear: “The Courts of the State of Missouri shall remain open.”

But not all our communities were equally impacted. So, my colleagues and I have tried to strike an appropriate balance between empowering local courts to conduct necessary business and the need to protect the health and welfare of witnesses, victims, jurors, attorneys, judicial employees, and all others involved in court proceedings. So yes, in-person appearances may have been suspended while others have been conducted remotely, but our courts have remained available.

In fact, Missouri’s legal system was better prepared than those in other states to handle the pandemic’s massive disruptions. We have spent decades creating statewide technology infrastructure, allowing continued electronic case filings and court determinations when in-person proceedings are not required. Thank you for your continued investment in this technology. It is not only the way we all do business, but as the pandemic has shown, it can also be a lifeline for Missouri citizens.

Two groups deserve huge credit for their efforts to keep our courts operating. Our state courts administrator’s office – and in particular its IT professionals – did yeoman’s work to get more than 400 judicial officers and thousands of court employees online, working safely from remote locations and using Webex to conduct court proceedings.

And the presiding judges of our 46 judicial circuits and the chief judges of our three appellate districts collaborated with other local leaders to determine how best to proceed given local circumstances. The challenges have been especially difficult on our circuit courts, where hyper-localized conditions might mean different buildings in the circuit are operating in different proscribed phases at any given time.

At the Supreme Court of Missouri, our work has continued uninterrupted. We had 20 days of oral argument last year, only two days fewer than in 2019.

We finished our March sessions just before the pandemic hit, and our April 14 argument was our first ever conducted by Webex. Although I think we’ve become more adept at these remote arguments, the most common phrase uttered still may be, “You’re on mute.”

While enduring illness, isolation, and quarantines, judicial personnel have continued to process and hear cases in remarkably innovative ways. Cases took a dip in mid-March, but after our circuit courts began implementing the statewide operational directives and guidelines in May, their ratio of cases disposed to cases filed for the remainder of the year was only 5.6% less than what their ratio had been in January. The other good news is that for the cases with designated time standards, our circuit courts timely resolved nearly 91% of them — not even 2% below the average from the prior four years! This is in no small part thanks to the courage and dedication of the court staff in all your local circuits. Let’s give them a big round of applause!

Some circuit courts were able to resume grand jury proceedings and petit jury trials with pandemic precautions in place. For example, after the Jackson County circuit court modified protocols and increased health and safety measures, 93% of its jurors reported feeling “very” or “fairly” safe at the courthouse. Similar protocols are in use elsewhere in the state. Since June, jury trials have been held in at least Boone, Butler, Cass, Christian, Greene, Henry, Phelps, Pulaski, St. Charles, Webster, and Wright counties. To facilitate social distancing, juries have been selected in locations ranging from schools and community auditoriums to National Guard armories to churches and even convention centers. In a Greene County civil jury trial held at Bass Pro’s White River Conference Center, a large stuffed bear in the room’s woodsy décor appeared to be the only audience member.

Our directives encourage local courts to maximize technology when possible. Many judges have held a number of hearings and other proceedings remotely. And some are experimenting with technology for trials as well. For example, the Christian County circuit court successfully held at least one hybrid jury trial in a civil case last fall, with jurors and lawyers in person and some witnesses testifying via Zoom. And at the Supreme Court, we have continued to provide audio streams of our arguments, both live and archived, as we have done for most of the last two decades.

Other Court Updates

While the pandemic has consumed much of our time and attention, it has not distracted us from continuing our other work. I am proud to report the Treatment Court Coordinating Commission approved standards by which every treatment court case in the state should operate. Those guidelines are being implemented, and all but one of our 46 judicial circuits now have some treatment court programs. Since their inception nearly 30 years ago, our programs statewide have had more than 23,650 graduates and more than 1,100 babies born to female treatment court participants. Of those, 1,020 were born drug free.

Our treatment court cases are also continuing during the COVID-19 crisis by way of remote technology. Boone County increased its treatment court culture of honesty during the pandemic by using telehealth for participants to interact with providers. In fact, Boone County has found remote technology has reduced impediments to participation by those who lack reliable transportation to the courthouse, increasing the likelihood for successful long-term treatment. The Jefferson County circuit court even held a Zoom graduation and sent graduation certificates by mail.

With respect to our criminal justice system, we held an initial leadership summit in late February 2020. We had planned to present a series of “Leading Change in Criminal Justice” follow-up meetings with assistance from the Missouri Justice Reinvestment Initiative, the National Center for State Courts, and the State Judicial Institute. The pandemic caused us to shift the series to a virtual format, featuring experts from around the nation. These virtual meetings have been occurring since August, with participants from 28 circuits so far including judges, prosecutors, defense attorneys, law enforcement officials, school administrators, and treatment providers.

Another ongoing project is my effort to improve the security of our state courthouses. The project is led by the Supreme Court’s chief marshal, Robert Stieffermann, whom we coaxed out of retirement from a stellar career of more than 36 years with our state’s highway patrol, beginning as a patrol officer in Iron, Madison, and Wayne counties and culminating at the rank of captain and as director of the patrol headquarters’ professional standards division.

Unfortunately, attention to security too often comes only in hindsight – whether it be a bombing of a public building in Oklahoma City or New York City; a bombing on the streets of Boston or Nashville; or active shooter incidents in churches, schools, malls, or concert venues in cities big and small throughout our nation. While COVID-19 put a damper on many things – including, thankfully, the number of active shooter incidents – the danger remains, and there still exists a need for preparedness against threats posed by deranged and menacing individuals in our society.

Although the pandemic stifled completion of our task, it is worth advising you of our preliminary findings. Our courts have identified critical needs for facility upgrades and additional security equipment, as well as additional full-time marshals and deputy marshals statewide. Our security staff need additional training and more standardized compensation. Our judges need to ensure their privacy can be protected, and, in my opinion, we need to be able to use witness protection services funds to protect judges and their families against credible threats of violence.

The bottom line is this: No public servant – whether a legislator, executive officer or judge, or any of our dedicated employees – should have any reason to be fearful in their place of work. Nor should their families be fearful at home. It is equally critical for all of us to protect our buildings and to ensure the safety of the many members of the public who have occasion to come into our buildings and courthouses for any number of reasons. As the tragic events in our nation’s Capitol building last month made painfully clear, security is an investment we cannot afford not to make. It is incumbent on all institutions to employ what our Marine Corps designates as a “left of bang principle” regarding security.

One final point of business, and another nod to our history. Next month, the longest-serving judge currently on the Supreme Court of Missouri, and only the second woman ever appointed to the Court, will be leaving us. My esteemed colleague Judge Laura Denvir Stith has granted me the opportunity to announce her retirement from the bench after nearly 27 years of judicial service and her reentry into private life. Her resume and body of work speak for themselves, but let me remind you she will leave the Court two decades after she was appointed. She served as chief justice from July 2007 through June 2009, and she will leave a lasting legacy in the areas of ethics, gender, and justice. She is a dedicated jurist. Her experience, intelligence, diligence, and wisdom will be missed. Please join me in wishing her all the best in her retirement.

Conclusion

Never could I have imagined a year more tumultuous than the last. As individuals, as professionals, and as a nation, we have been tested to our limits. Collectively, we have suffered, while attempting to juggle work and school from home. The pandemic has caused not only lingering illness and death but also isolation that, for some, has been too much to bear.

But as we stand here today in Missouri, on the bridge between our last 200 years and the next, remember how much we have overcome and how well our ancestors persevered – indeed, thrived – to bring us to where we are today. Our strong institutions and collective history prove that necessity, ingenuity, and intestinal fortitude bolster the human character and ensure our survival. So, I am certain the perspective of the past provides strength to endure our present time of pain and gives us hope for our future. Through continued communication and collaboration, I know that future will be bright.

The state of our judiciary is healthy. May you all stay healthy and well. Thank you for your public service.